Leadership and cultures of belonging are both hot topics, both vague, and both essential components of the other; cultures of belonging are the result of good leadership. Leadership can be hard to unpack because it means different things to different people. For years I ignored thinking about leadership because it was too ambiguous and confusing to apply — certainly to myself. I also saw too many leaders with too few qualities I considered admirable.

In organizations, we conflate leadership with executive roles. Many executives, however, are constrained in their ability to lead because of the governance structure in which they operate. They are legally and financially responsible for organizational assets and punished for disruptions to those assets. People and their human needs are disruptive to that legal and very real responsibility.

The implication?

While executives certainly have the ability to change how assets they control are allocated, they have very little ability to change the system around them. Where executives sit in the hierarchy determines what they can change. As complexity increases, the work of different groups within organizations becomes more interdependent and constrains the ability to change things even more. It’s a frustrating time to be an executive because while you have explicitly defined expectations, control over outcomes and impact is diminishing. This dynamic has led to a corp of executives hired for stability rather than leadership and unsuited to the massive challenges currently facing all organizations.

So What Is Leadership?

I have reflected a lot more about leadership over the years and oddly, find myself doing leadership coaching. We have a leadership crisis in the United States right now across many sectors and I think its root is that we are conflating too many concepts.

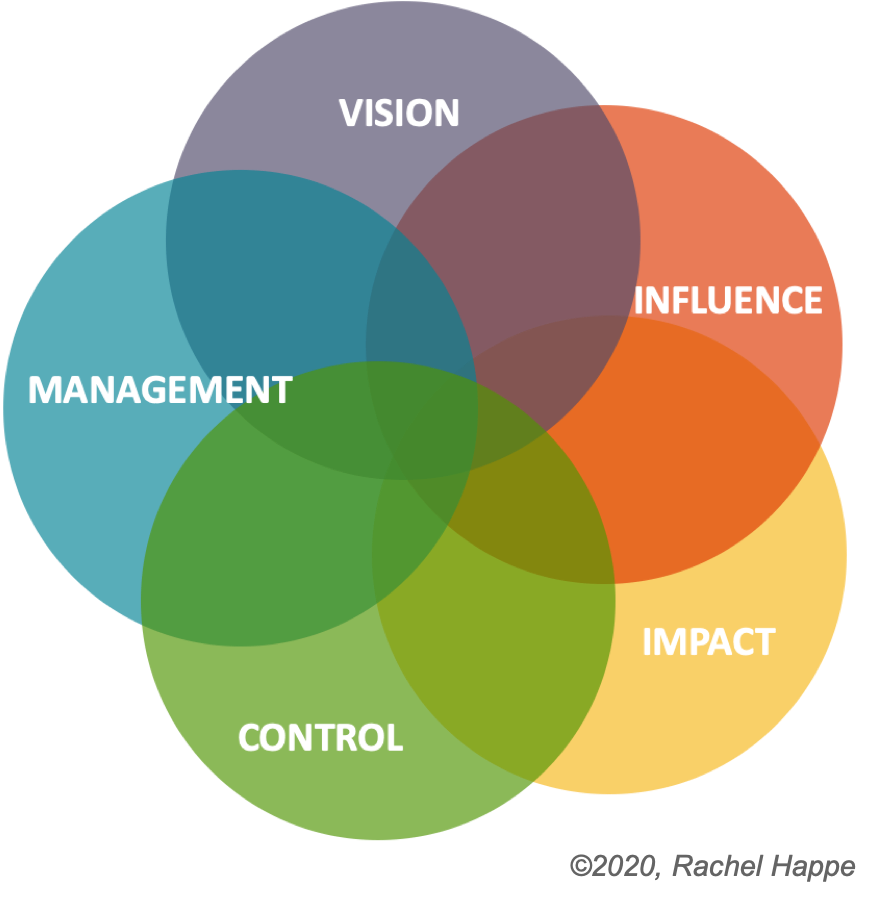

We get leadership confused with a few different characteristics; control, management, vision, influence, and impact. Those are all different things that can co-occur but require the ability to negotiate the inherent tension between leadership vs. control, power vs. influence, and vision vs. impact. It’s a tall order. The ability to manage effectively in the traditional sense and be good at vision and influence are very different competencies. Here is how I think about each:

CONTROL: simply put control is ownership of assets and wealth. In public companies, shareholders are the owners, some of who are also employees. In private organizations, ownership is often divided in a number of ways; from sole ownership to more distributed employee ownership. The more of ownership a person has, the more control they have.

MANAGEMENT: management is the application and control of assets on behalf of owners. Executives, more than anything else, are managers. They are responsible for using assets effectively on behalf of owners and regularly reporting on progress.

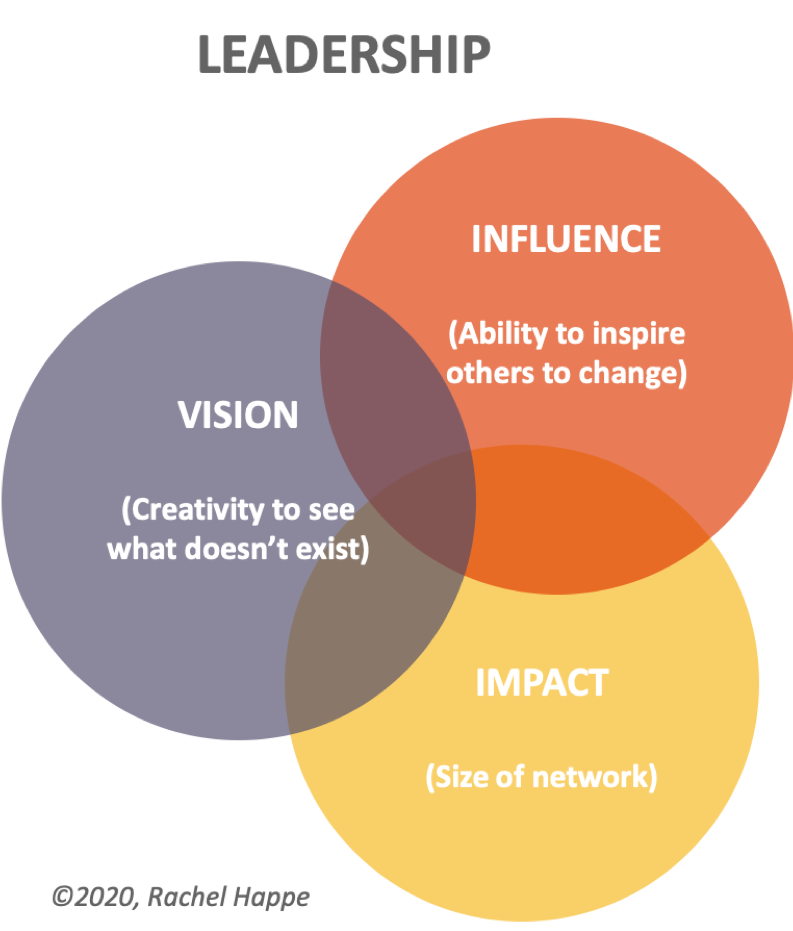

VISION: vision is the ability to see how something could be different and better. Vision requires creativity, experience, and perspective. Individuals can be great at vision with have little ability to realize it. Vision is not enough to be a leader and vision often gets in the way of management because it invariably creates friction between the way things are and the way things could be.

INFLUENCE: influence is the ability to change someone else’s beliefs or behavior without force, manipulation, or explicit rewards. Influence is the core of great leadership. A person with influence and a small network, however, is constrained in their ability to lead by the size of that network.

IMPACT: impact requires a large network of people who both influence a person and are influenced by them; a community of relationships. The bigger the community, the more potential impact a leader has but as the community grows, impact is often limited by structural control of resources.

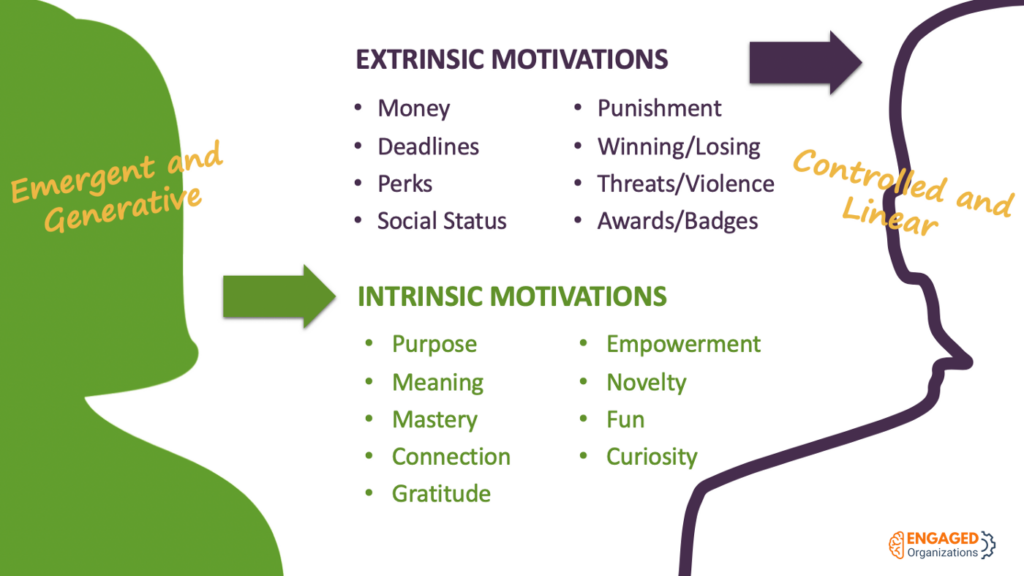

Leadership and control are fundamentally different techniques used to manage. Leadership is the use of intrinsic motivators and relational power to influence behaviors and outcomes. Control is the use of power and structural resources (extrinsic levers) to influence behaviors and outcomes. We confuse the two because we tend to measure outcomes rather than behaviors, engagement, and processes so the two can appear to be the same. In organizational language (aka accounting), the two appear the same.

Control is Self-Destructive

Using control to ensure outcomes is a predictable way to plan and build; we can accurately gauge what we have to invest in order to get results based on past experience. It’s a linear economic model. It’s easy to manage, which is important because it’s easier to find managers who can manage predictable things. The problem is that predictable is… well… predictable. It is like Dr. Doolittle’s famous Pushmi-pullyu and will always bend toward equilibrium. We will get exactly what we pay for — nothing more and nothing less. It hedges risks but it also hedges potential. The only way to get more out of an organization – to increase our growth rate – is to manipulate the system around it. System manipulation is achieved through things like government subsidies, taxes policy, regulations, and industry consolidation. In systems designed for growth in outputs, this manipulation becomes inevitable. As manipulation of the system increases it becomes top-heavy, rigid, and self-destructive.

The antithesis of control is leadership. Leadership is collaborative and inspires others through intrinsic motivators; meaning, mastery, empowerment, novelty, and connection. Things that cannot be owned and are not finite. Leadership increases by inspiring leadership in others. Using leadership to effect impact is limitless because it creates a positive feedback loop of belonging, engagement, and creativity – all the things that generate breakthrough changes and innovation. But there is a catch that keeps many organizations from harnessing leadership; its influence is not predictable, cannot be forecasted, and cannot be confined. There is literally no room in organizational budgets for the space to lead, which in practice looks like time to reflect, read, engage in unstructured conversations, and in experimentation. Intrinsic motivation languishes because of the way most organizations are managed.

Requirements of Successful Leadership

Leadership is vital for distributed organizational models, which are now possible because of technology. It requires organizations that empower employees to self-manage and make decisions at all levels. In short, it requires that all employees have the opportunity to lead. This leadership is characterized by behaviors not by role and which includes the ability to:

- Cultivate a sense of belonging in others that calms their anxiety and encourages them to share their unique perspectives.

- Prioritize and protect the time to reflect, experiment, engage, and rest.

- Make ambiguous decisions that balance the needs of multiple stakeholder groups.

- Be motivated by the growth, success, and recognition of others without the need for credit.

- Navigate paradoxes and tension.

- Engage people in ways that prompt them to learn, experience, and experience new insights.

- Identify and communicate a meaningful vision that inspires others while also adjusting it in response to feedback.

- Emotional energy and enthusiasm for what is possible.

- Ignore competitive pressures and keep people focused on addressing the vision that inspires them.

- Accept messiness as a critical part of the process.

Consider the current individuals you think of as leaders and whether they have these qualities. Do they make others feel important and valued for their unique strengths? Do they use more engaging or declarative language? Do they feel responsible for having the answers?

Most organizations today are saturated in stress, competition, anxiety, too much process, and an inability to navigate conflict. They are not toxic cultures for individuals. Great leadership creates cultures of joy, connection, and excitement; they keep the organization looking toward the future rather than trying to improve on the past. Great leaders use social and relational sources of power combined with structural power to increase their reach and impact.

Manage the Environment, Not the People

In the industrial era, most innovation was in the production of goods. Growth and profitability came from standardized production and the production of more goods in less time at lower costs. People were primarily parts of that mechanical system — filling in where technology was not yet advanced enough. The production economy is now largely commoditized and serviced with machines, robots, and algorithms. People make sure the systems run and use creativity in marketing and sales but are a smaller and smaller part of the value chain for standardized goods and services.

People are looked to now for their unique mental and emotional abilities — not their physical contributions. Empathy, emotions, and creativity are all assets that are unique to people but are discouraged rather than valued in most jobs. These unique abilities thrive when people feel seen, heard, inspired, cared for, supported, challenged, and excited. They are not optimized with extrinsic rewards or punishments. They are what drive innovation, collaboration, relationships, and trust.

If the future success of organizations is their ability to innovate, management needs to change. But how do you manage in this dramatically different type of culture? This question drove me to start and build The Community Roundtable in 2009. I saw early community management leaders harness the power of networks to create value that was mindblowing; platforms like WordPress, which powers 43% of all websites and Wikipedia, which includes 6,548,530 (as of this writing) articles in English alone. I wanted to know how the facilitators, moderators, and community teams successfully managed these communities to achieve such complex and high quality outcomes because I saw that networked communications technologies and platforms would soon enable any organization to operate in a similar fashion in ways that optimized their output and made them agile and adaptable.

After over a decade of conducting and publishing annual State of Community Management research, which explored the ways community organizations worked. This research revealed how we can successfully manage work in a different way, which often led me to say that the future of all management is community management. These community management leaders were and still are underappreciated in what they can achieve.

Successful community managers can inspire and organize immense value creation from thousands or tens of thousands of individuals with very few full-time staff. How? They manage the environment, not people or tasks. Community managers ensure that the leadership, infrastructure, resources, metrics, and routines are all set up to make the work of the community easy, satisfying, joyful, and rewarding. They make sure each individual contributor receives more than they contribute by engaging in the work of the community. They ensure that the culture of the community welcomes, accepts, and supports people.

Community leaders do all of this without telling people what to work on or how.

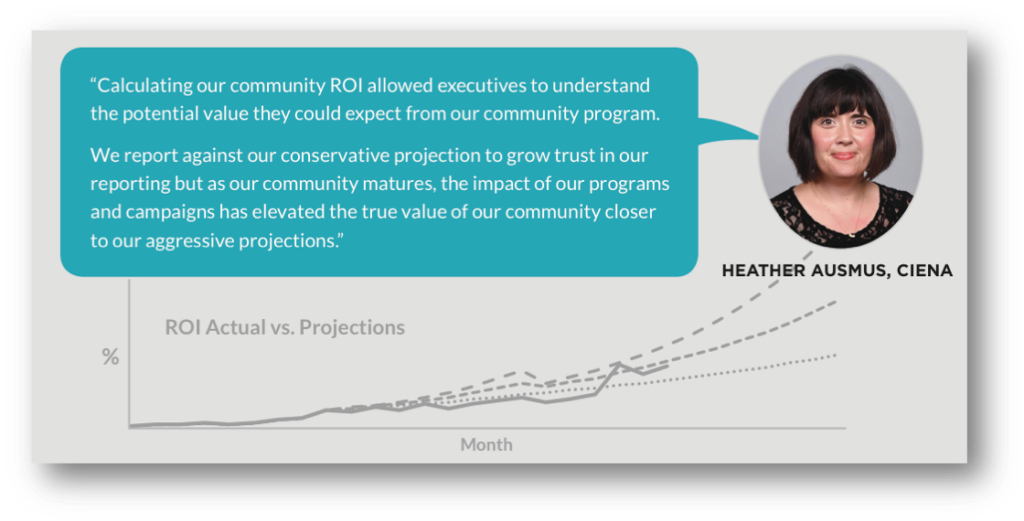

Using a community operating model creates cultures in which people want to participate. Engagement grows because individuals get something more valuable than what they put in. People commit to each other because they form authentic relationships. People collaborate to build incredible things because it challenges and excites them. Perhaps most compelling is the impact of community operating models on business models. Community models generate unbelievable ROI because community-centric governance is much lighter than what currently exists in organizations – all for the ‘cost’ of giving up control.

Organizations that want employees to feel seen, accepted, and validated – to create a sense of belonging – would do well to learn more about community management because it is the key to transforming organizations.

Managing organizations like communities are what will inspire people to do their best work people by ensuring they receive attention, care, support, curiosity, inspiration, and excitement through authentic relationships with others. Optimizing organizations for this connection requires dismantling the heavy, layered governance that currently controls people and replacing it with governance that frees people to work collaboratively with more control, influence, and choice in how they work.

Leadership, Communities, and the Future of Work

Control over people no longer works in an age where we can connect with anyone, find information easily, and work remotely. Talented individuals will join organizations where they can satisfy both their extrinsic need for money and their intrinsic need for meaning and challenge.

Organizations that do not adapt to this new reality will lose traction because people do not want to be controlled. Control is also expensive, requiring layers of management, policies, infrastructure, and accounting mechanisms that shear investment resources away from value creation.

Communities are showing us what the future of work can look like — and it is compelling

To see what enterprise community teams are achieving, see Engaged Organization’s Digital Workplace Communities report.

[pvfw-embed viewer_id=”1774″ width=”60%” height=”800″ zoom=”auto” pagemode=”none”]

Helen Blunden

Many thanks Rachel for this thought provoking post that challenges us to rethink the original view of leadership. What are your thoughts when it’s not about “control” in the standard definition of the word? (My observations that even how “control” is defined/demonstrated can vary and now it’s more akin to personal belief and alignment). For example, when leaders don’t actively role model the behaviours themselves or support those who do but will actively promote community engagement to others when…prompted.

Rachel Happe

Control is such an interesting topic and concept that no doubt means a lot of different things to different people. If I understand your question, you are thinking about leaders who may be successful at prompting engagement even if they don’t ‘walk the talk.’ Depending on the context that likely mixes intrinsic & extrinsic motivations; i.e. “that person has some structural influence over my success so I’ll try to make her/him happy by engaging.” I don’t think that will ever match the power and value of combining intrinsic and extrinsic motivators (I get something tangible back AND it is meaningful, fun, challenging, etc.)