Strategy is Dead

Like Voldemort, traditional strategic processes have been crippled and revived many times. With each new evolution of the economy, it becomes clearer that the legacy approach to strategy is constraining, rather than supporting, potential. Top-down, opaque, expensive, anxiety-producing, and largely determined by an old, white mens’ club of executives, board members, and their consultants. This process is propped up by outdated corporate governance – legal, accounting, and reporting requirements – that are slow to change because of the thicket of reinforcing interdependencies between them.

But the world is changing. With each line of code, the rate of changes increases incrementally. As it does, the difference between markets and organizations continues to diverge. As this gap broadens, it asserts ever-greater friction and stress. So far, that stress has mostly resulted in employees driven to work harder and longer to try and keep up.

Control is for Amateurs

The traditional approach to strategy – at its best – takes between 6-18 months to plan and implement. This process is typically outsourced, costs companies millions of dollars, and goes somewhat like this:

- Interview stakeholders and conduct research

- Collect and review industry and financial market research

- Generate analysis based on an array of frameworks

- Secure agreement on strategic objectives

- Create a gap analysis between the current state and future objectives

- Develop a restructuring and implementation plan often driven by the financial balance sheets of each business unit or functional group with little regard to their interdependencies, which are too complicated to easily assess.

- Give the impacted executives marching orders.

- Call it a success and initiate the next round of strategy.

Guess what? In the 18+ months of creating and implementing a strategy, markets shift – sometimes significantly – and the process does little to increase confidence, clarify direction for individuals, or reduce anxiety. If anything, it weakens cultural cohesion and trust.

If the old methodologies no longer work – and are actually doing more harm than good – what is the answer? The most common answer is to increase the speed and intensity of the existing process – but, as I suggested in 2011, that will break your employees and do little to keep up with the market.

People with the hierarchical, controlled, and regulated mental model of how organizations operate have a hard time seeing any other option than the way strategy has always been done. After all, an organization still has to respond to market opportunities and customers. An organization still needs a clear, guiding direction on what it will and will not pursue. Employees still need to be organized to create, deliver, and support products. The organization still needs measures of progress.

How can all of that be accomplished without intense research and detailed planning?

Playing a Different Game

The legacy of European economic and social models is so immutably fixed for most people in the United States that it is hard to change our approach to organizing. It bleeds through every aspect of how we manage organizations and is generated by assumptions about human nature. Assumptions like:

- The need to compete and the related anxiety and paranoia that if we don’t win, we lose.

- The scarcity and subsequent hoarding of resources.

- The need for paternalistic oversight, monitoring, and discipline of others in order to get work to happen.

- Things, transactions, and property have more value than people, interactions, and relationships.

This mental model is toxic – but not inevitable. How do I know that? I have been in plenty of environments where those assumptions do not exist and while they are pockets in the wider ocean of society, there is no reason they need to be the exception. Margaret Mead addressed this in 1940 in her essay, “Warfare is Only an Invention — Not a Biological Necessity.” In short, we assume things because we are brought up in a society that assumes these things.

What does that have to do with organizational strategy? Pretty much everything. Our organizational strategies make assumptions about market and organizational (human) dynamics, about the need to compete and lock other organizations out in order to be successful, and about how we need to structure organizations to make sure work gets done. If all of those assumptions are wrong – and I maintain that they are – then our organizational strategies are built upon a faulty foundation.

What if we assumed instead that:

- There is room for all of us to thrive and not winning does not mean losing.

- We don’t need to hoard things because there is opportunity for all of us.

- People willingly and joyfully create value if they get more back than they contribute.

- When people are motivated to contribute, they produce more value than they will when forced or coerced.

- Without coercion, anxiety dissipates and opens up opportunities for ideas, connection, discussion, and innovation.

- When people willingly contribute there is no need for a huge swath of governance and infrastructure designed to monitor output.

- Assessing the engagement, interactions, and behavior will show the health and potential of the organization.

What would strategy look like using those assumptions?

A Different Kind of Strategy

Shifting assumptions changing the focus of organizations from objects and transactions to people and relationships. Relationships with and between customers and employees. Healthy people and great relationships will ensure success because they will have the time to hear each other, know each other, and care about each other. The products, value, and support will follow. People (employees or customers) won’t often stay for a product – but they are likely to stay for great relationships.

Trust becomes the web that aligns employees and the organization with its market instead of plans, governance, contracts, and rules. That web of trust is more flexible and adaptable. Governance and contracts don’t disappear; they are critical to ensure shared expectations of boundaries and the value exchange but they are the codification of the trust and relationship rather than the determinate of it.

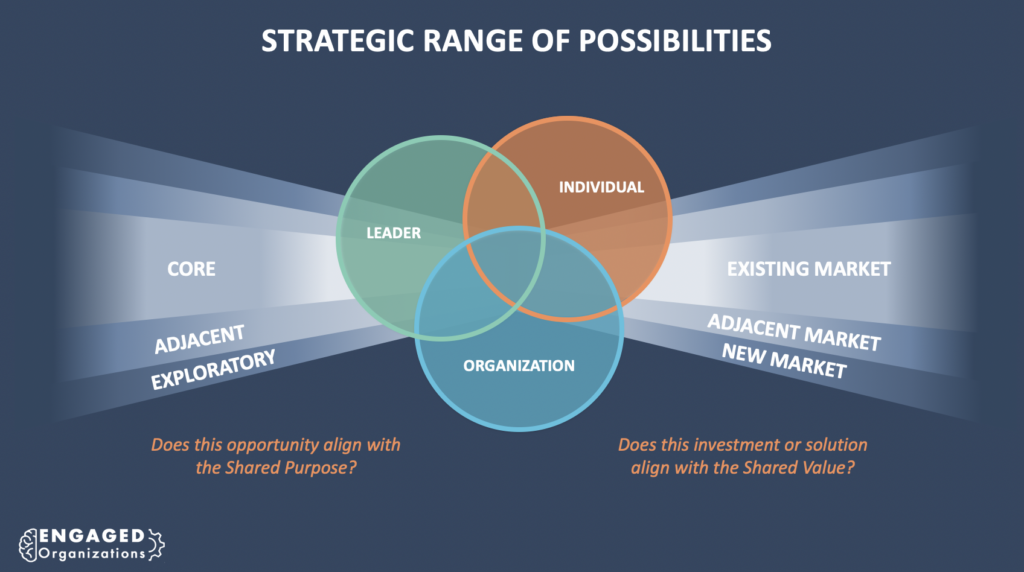

If the system is connected by trust, the strategy becomes much simpler. The strategy defines where the boundaries of the organization and its market are. Individuals and customers are empowered to make decisions about whether and how they participate; what value they contribute and what value they extract. The constraints created by centralized heirarchy and governance fall away, allowing the organization to pursue many more opportunities.

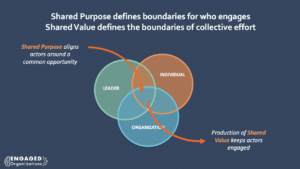

The strategy is the gravitation pull that ensures cohesiveness and to do so, it must be concise and clear; a network of people is not going to read a 90-page strategy presentation. At its core, a networked strategy defines the shared purpose that brings the organization and its market together and the shared value that is created to makes the organization and its customers successful.

This strategic core empowers individuals in the network to answer the following questions:

Does this opportunity align with the shared purpose?

Does this investment, effort, or solution align with the shared value?

I evaluate company mission statements through this lens and it’s interesting to see how well some answer these questions. Tesla’s mission is “to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy.” As an employee or customer that is a well-articulated and compelling shared purpose. In comparison, Coca-Cola’s mission to “Refresh the world. Make a difference.” An employee is likely to struggle to make a good decision about what opportunities or investments align; is Coca-Cola interested in the swimming pool business? It too is refreshing.

When I work with clients to define shared purpose and shared value statements I ask them to find five people who are excited by them as the first test of effectiveness. It seems like a radically simple test – but it provides great indication about whether the organization and its ecosystem can create energy that draws people in. If that first hurdle is not or cannot be met, there is work to do. That work is not about creating a more detailed strategy – it’s about collectively figuring out how the company wants to participate in the world and who it is as an organization.

Applying a Shared Purpose and Shared Value Strategy

Once the core of a network strategy is defined, there is obviously a lot more work to do – and it is, of course, where things get interesting. An organization that is highly structured cannot jump immediately to a largely self-aligning network. Because of the culture, norms, and expectations of employees and customers removing layers of governance all at once would likely result in chaos. Employees have internalized management control to such a degree that many fear making decisions and it’s no wonder – that initiative is so often punished culturally in organizational cultures today. I am often reminded of Mary Barra’s change to the dress code at GM from a multi-page document to two words, “dress appropriately.” She was surprised how much managers objected because it was easier just to tell people what to do and much harder to help them understand appropriateness. Chances are, however, helping employees understand appropriateness came with vital information about who GM is as a company.

Unleashing an organization from governance constraints requires a circuitous process; making small changes incrementally then giving people time to acclimate to the new power dynamic. While few people will come out and say they like detailed processes and governance, it limits individual accountability and with it risks for individuals. Trust is hard. It builds slowly by being tested to ensure its freedom doesn’t later result in punishment. Decades of weaponizing work relationships mean that it will take investment – human investment – to ensure individuals feel safe to take the risks and to test the trust they are given.

To truly transform an organization’s culture is an expensive, messy, and time-intensive investment. It’s not impossible but it is hard. Most organizations will not have the courage to try – and will continue to invest in technology or re-organizing the company, hoping that will be enough. While those efforts may help the CEO reach short-term profitability goals, they are unlikely to ensure an organization’s longevity. It is time for boards to decide if they want short-term profits or strategic resonance, something Indra Nooyi balanced particularly well at Pepsi.

The pandemic and the virtual work that came with it gave employees a small taste of the flexibility that is possible and from all accounts, many do not want to return full-time to the office. That hybrid work world will require organizations to operate on a foundation of trust – and as Tsedal Neeley confirms, leaders will need to be explicit in building it. We are facing a unique opportunity. Employees are creating a groundswell of interest in changing how they work – will organizations use that energy as an opportunity to reach an inflection point; gaining support and commitment to adapt in fundamental ways? Or will they go back to rearranging the furniture, hoping futility that things will return to ‘normal?’

As Andy Grove suggested there is not really a choice, “Adapt or die.”

Question of the Month: Strategic Planning – Engaged Organizations

[…] iterative, evolving, and done by many more people than have been included traditionally. The lengthy and expensive process of research, interviews, development, and rollout will fade away in large part because formal research cycles can't keep up – customer communities can provide much […]