Trusting cultures require intentional and constant moderation. As I was writing this, Frances Haugen was testifying before Congress and discussing how Facebook knowingly allowed destructive content to flourish on its platform because anger, criticism, and attacks all prompt immediate reaction – and a lingering emotion that prompts people to return even when they know it is negatively affecting them. Facebook’s business model is predicated on views – and strong reactions, particularly strong negative reactions, drive views. Facebook has little economic motivation to remove the vast majority of socially destructive content – and seems to have no ethical motivation to do so either, given their monopoly over the world’s social graph. It is not hyperbolic to say it is destroying our society.

Destroying Trust Destroys People

Destroying trust – whether in a society, country, organization, or family – has dire consequences for individuals.

That instability inflates anxiety, depression, violence, and self-harm and more critically, keeps us from each other, which ironically is how to remedy feelings of division and anxiety to regain emotional stability.

A wide range of negative consequences and issues are related to poor connections with others and lack of trust. We have known this for a long time – one of the most heartbreaking things to watch is the experiment Dr. Harlow did in the late 1950s that took love and attachment away from a baby monkey and then gave it the choice between food and a fleece-covered wire ‘mother’ – it chose the wire mother. Social media algorithms are doing a similar thing to all of us, only in a much more insidious way. Social media companies are taking advantage of our deep need to connect and then twisting that connection into a web of negativity, which sets off an accelerating doom loop. The most vulnerable are most likely to get caught. Instagram, for example, has been shown in internal Facebook documents to cause significant negative thoughts in 3% of teenage girls, resulting in depression, anxiety, or self-harm. Worse, the more depressed a teen is, the more they come back – driven by that deep need to connect. That natural and healthy instinct to connect, which helps alleviate anxiety and depression, is being used to serve them more destructive content. It is abusive, maniacal, isolating, and very difficult to get out of the cycle. It is on the verge of sadistic.

Moderation Is Not Enough

Behavior of any kind, when done in groups, creates feedback loops. Individuals ‘mirror’ the behavior of others, especially those in positions of influence or authority. Mirroring is an unconscious copying of another’s gestures, words, and behaviors and it is the brain’s way of aligning and connecting with others – in effect saying, “I support and like you.” That mirroring creates a feedback loop; the more people who act in a certain way, the more people act that way. This dynamic is what drives tipping points in networks and is a key element of understanding behavior change. As tipping points are reached, the spread of a behavior accelerates because there are more people to mirror. This happens with both negative and positive behaviors but it is easier to artificially trigger negative behaviors, making it an easier and cheaper behavior change – and part of what makes negative behaviors so pernicious.

Moderation is the activity of arresting, discouraging, and giving out consequences for negative behaviors – behaviors that make a discussion, a space, or a culture unproductive or unsafe. The way different networks moderate depends on legal regulations, the business objective, and the business model of the network; combined

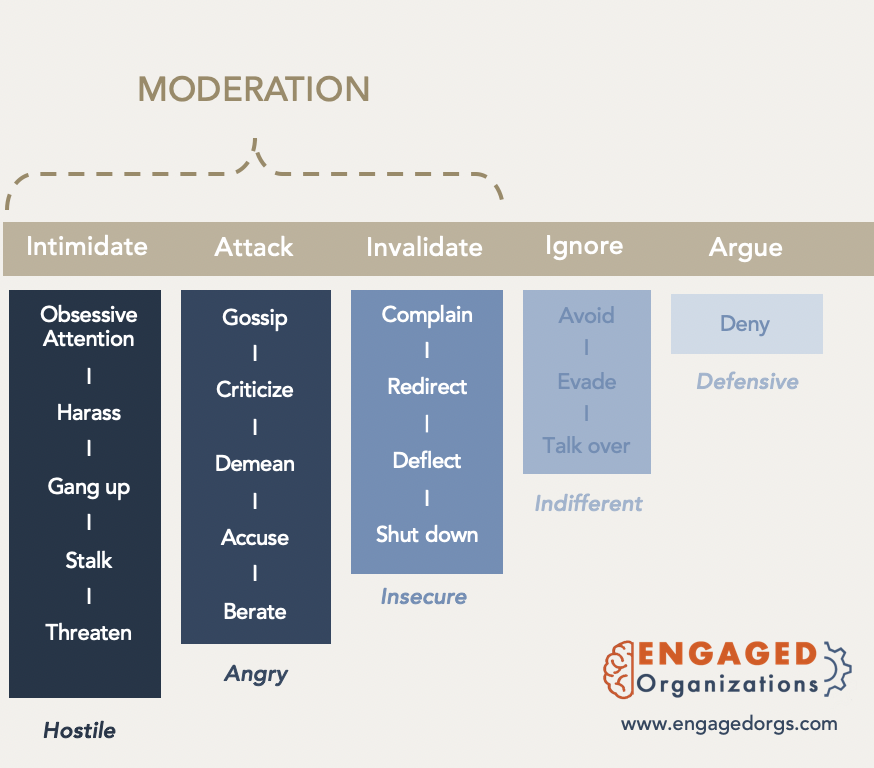

each community or network has its own moderation standards. These standards define the behaviors that will result in warnings, suspensions, or ejection from a community. While there is a broad range of behaviors that decrease the value or safety of a community – seen in this chart under the categories of arguing, ignoring, invalidating, attacking, and intimidating, most moderation standards tend to cover only the worst behaviors, those that attack and Intimidate others. The less harmful behaviors are typically tolerated – or addressed informally and inconsistently with warnings or reframing.

Moderation teams and tools in private spaces can ban, restrict, or remove any content and behavior they see as outside the boundaries of the network or community. When they decide to let a negative behavior go without acknowledgment those negative behaviors can quickly saturate a population, especially if they are started by highly active or influential members of the network. Once that behavior takes over, it is often almost impossible to rein in unless the company is willing to suspend or remove a good portion of a community. This is clearly not appealing to Facebook and we can’t do that with people in our local communities either. The easiest way to keep it from happening is to not let it happen from the beginning.

Moderation is a critical tool – it maintains the threshold for the least acceptable negative behavior and protects the community from the doom loop we are seeing on Facebook. However, the absence of negative behavior and content does not, on its own, create positive engagement and culture. It can neutralize behaviors but it does not ensure a community thrives.

Restoring Thriving Communities

Individuals fail or thrive as their communities fail or thrive. At their worst, communities hold people in a negative loop that harms them and from which they cannot escape.

This understanding makes fostering healthy community cultures imperative for any group, organization, or society.

The million-dollar questions are:

- How do you foster a community so it thrives rather than spirals?

- How can you move a community culture from a toxic to neutral to thriving?

In Facebook’s response to Frances Hogen’s revelations, they wrote, “If any research had identified an exact solution to these complex challenges, the tech industry, governments, and society would have solved them a long time ago.” They imply they do not know – and yet is it clear that they DO know how to adjust their algorithm in ways that increase or decrease engagement behaviors. We do know how to do it, it is just not easy and the value is not in the quantity of engagement but the quality so until our metrics – and associated business models – are architected around different metrics, this problem will persist. Community management is the emerging discipline that can help organizations understand the opportunities and trade-offs in designing communities for different objectives. When the objective of a community is the quality of engagement, negative engagement is corrosive to making a community safe for richer relationships, more meaningful interaction and deeper collaboration.

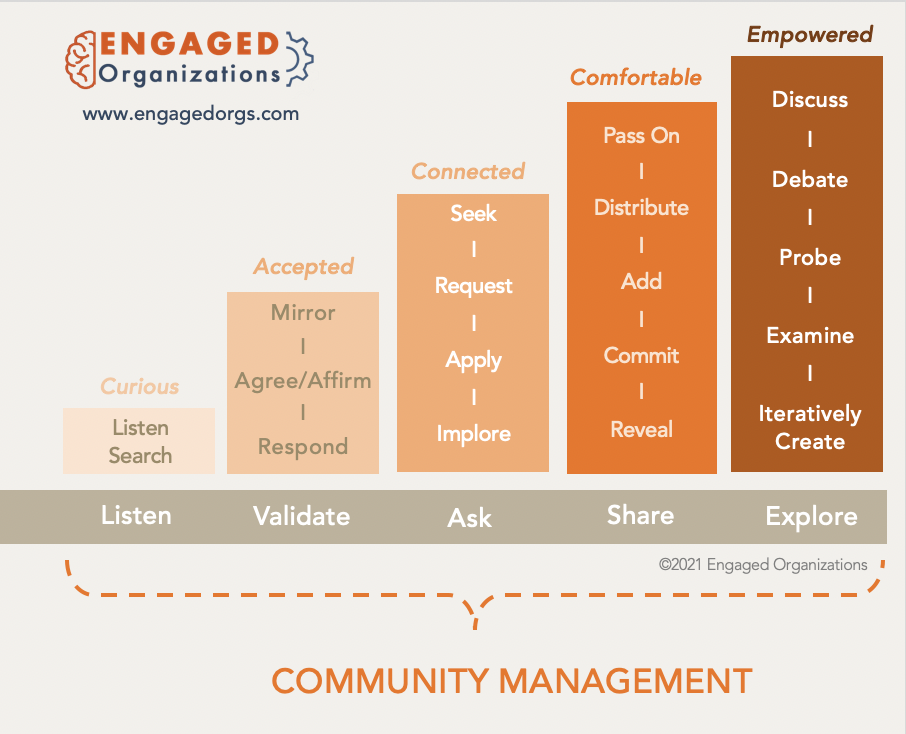

While moderation discourages or eliminates negative behavior, that is not sufficient to increase positive, constructive engagement. These engagement behaviors include listening, validating, asking, sharing, and exploring, as defined in this chart. Community management is focused on fostering positive behaviors that support any objectives more complex than driving impressions or clicks. Good community management requires leadership and resources to produce the experiences, events, and reactions that inspire positive behaviors. It is the effort to ensure people are supported and challenged to engage more deeply and ultimately, become leaders themselves. It is helping those in the community feel accepted, connected, comfortable, and empowered so that they can support each other, ask questions, share their perspectives, and explore differences. It takes time and resources – either paid or volunteer.

Thriving communities feel very different than most social networks do – they are emotionally calm and not as frantically active – as well as helpful, relaxed, fun, and supportive. Nothing feels forced or manipulated and every individual can choose how and when they participate. A great community feels like scaffolding that encourages joy, growth, and discovery. Engagement is typically less repetitive and frequent but much deeper in quality. Ultimately, thriving communities are meaningful – doing something for their members and the organization or world around them that make members feel good about themselves, valued by others, and part of a positive change.

Investing in Community

Community management doesn’t just happen. For thousands of years, it has required leaders to step forward to host events, start conversations, check in on others, collaborate on big projects, and listen. Unfortunately for our culture, community work has been too often ignored or dismissed. It is not hard to identify why – it’s the emotional labor often done by women but not recognized and articulated, let alone valued. As women have joined the world of paid labor, community management capacity in our local communities has declined significantly. Slowly, some organizations have realized that this is something worthwhile – that it generates the connections and trust that helps their organization succeed – and have funded enterprise community teams. But that has been a small minority of organizations.

Organizational leaders don’t like the investment required for community management because it seems squishy and it comes well before any benefits, which are complex and hard to link back to the investment directly. It takes time for relationships to deepen. It’s easy to ‘wait and see’ if community management is really needed, although because of the nature of feedback loops by the time it’s obviously needed, it is probably too late.

Some executives are pushing employees to go back to the office so their culture doesn’t suffer, not realizing the office has little to do with it other than that some employees are relied on to do the emotional labor of facilitating connections with no acknowledgment or reward. A number of years ago, I was talking to a group of executives and they were considering hiring an enterprise community manager. They were asking me about the qualities and skills of a great community manager. After listening to me for a bit, one of the attendees suggested that a woman who had been let go just months before would have been perfect for the role and that it was a shame she was gone. My guess is that she was doing this work intuitively, which was sometimes getting in the way of her other work, and she was seen as underproductive. We have minutely accounted for so much of employees’ time that there is no room for engaging and contributing to community building. Community building – things like spending a few minutes checking in on a colleague or organizing Friday lunches – is often discouraged if not explicitly punished because it is seen as wasting time. It is no surprise why trust is so low – but it is exactly what is needed to reduce anxiety, which opens up the pathway to learning and collaboration.

TLDR; What Can I Do?

What you can do to improve a community or a culture will depend on your position in it and the resources you have to offer. As an individual, you can always find opportunities to contribute positive ripples into your environment. If you have structural influence, consider ways to transition your organization or group to a relationship-first way of operating, that emphasizes jointly created, high-quality, and trusted outputs instead of focusing on a higher volume or size of outputs. In a world of content overload, We don’t need more content and documents – we need more co-created, understood, and trusted information. Most employees are still stuck in both a mindset and environment that prioritizes production, not trust.

Here are some ideas

If you are an individual:

- Don’t ignore poor behavior; you don’t need to confront or punish it personally but make sure the person doing it knows you see it and hears you note it to others.

- Actively take the time to see and acknowledge and promote positive contributions around you – and make sure others see it too.

- Validate and highlight the good ideas contributed by others – and credit them.

- Plan events that connect and support colleagues; this could be Friday lunches or a monthly co-mentoring group.

- Ask poeple about themselves. Don’t be the limp conversationalist and make the other person do all the work. Be the person who knows if those you work with have something stressful going on in their personal lives and make room so they can take care of it as needed, which doesn’t mean prying for details – it just requires a little sensitively to how people are showing up to work.

If you are a manager:

- Schedule regular time with those you manage to have casual one-on-ones. Ask them about themselves, how they feel, what is energizing them, and what is sapping their energy. Offer to help them mitigate issues and find more opportunities for the things that energize them.

- Get your team out of the office, together, doing just about anything. Ask people for ideas. Bring some energy (and yes, fake it if you have to). Try just having fun. Extra credit: ask a different team members every moneth to volunteer to plan a team activity based on something they love (and give them the time and budget to do it). That will energize them, help them practice leadership skills, and validate their value as whole people.

- Be aware of how your words and behaviors impact your team – and reduce those things that increase anxiety. Take the time to praise constructive behaviors publicly.

- Ask one team member every meeting to share something about their work – not deadlines or deliverables but what they are learning, why it matters, and how they navigated issues.

- Ask questions in meetings – and listen. Leave awkward amounts of space so other people talk (this is hard). Spend less time in meetings focus on deliverables and due dates and more time on HOW people are approaching problems.

If you are an executive:

- Reflect on what energy drives your business – and what helps to accelerate that energy. What kind of trust and relationships are required to do that well? What kind of time do people need to build those relationships? Who is in charge of making sure those relationships are fostered?

- Assess the things that cause the biggest frustrations and generate the most energy for employees, part of which can be done by measuring the amount of postive and negative enagement behaviors in your organization. Prioritize the strategic business opportunities that energize the organization. In a complex marketplace, many options are plausible but the one people are most engaged with will be the most successful.

- Invite outside perspectives, whether from peers at other organizations, consultants, or analysts. It is almost impossible for anyone in an organization to see all of its opportunities and challenges.

- Suspend disbelief and don’t assume that what has worked before will work again – the world is constantly changing.

- Allocate resources to a work optimization group that supports business units and groups in redesigning the way they work, rationalizes tools and governance, and works with employees to ensure changes are sustainable and broadly practiced.

Fostering positive cultures is both easy and deceptively complex. Easy because none of the behaviors, on their own, are hard to do; hard because behaviors are encouraged and reinforced by governance which is difficult to change. It’s easy to change the behavior of a small group for a short period of time – but they will revert to old behaviors if the governance is not adapted to reward the new behaviors. It can be a vexing cycle if not given the significant support needed to overcome and remove the governance hurdles.

Perhaps the best question to ask yourself is whether you have the courage, energy, and fortitude to invest in this work? Most will wait until their house is consumed in flames, metaphorically speaking.